Last month I attended the Oil and Money conference in London. I used to attend fairly often but this was the first time in a few years. Oil and Money is not a large conference but it has high-level speakers and is normally at its best during uncertain times – but not this year.

The speakers generally include Chairmen/CEOs of major participants in the international oil and gas industry and this year was no exception. Speakers included top executives of Shell, Total, BP, OPEC, Qatar Petroleum, the four largest oil traders, and others of similar stature. Such a roster is expected to present some bold forecasts, significant announcements, controversial viewpoints, and food for thought and at Oil and Money it usually does.

This year it was apparent early on that these organizations are not defining the conversation and they know it. Most of the commentary was how these organizations will respond to trends and events of which they are not the driving force. These large organizations have become responders; not initiators and it is apparent they do not know what they will need to respond to next. They are not leading the industry into new supply, marketing, or pricing relationships; they are not coordinating with political efforts to establish stability in areas of weak, ineffective, or corrupt governments or upheaval or conflict; nor are they leading technological advance.

As I have noted before, the oil and gas industry is in a period of transition. As the largest component of international trade it is subject to numerous cross-forces imposing tensions and uncertainties: Trade conflicts; political conflicts between the US and Iran, Russia, and China; unreliable data; critical elections in several countries evidencing fundamental political re-alignments; a booming US economy coupled with slowing European and world economies; resentment of the international finance and monetary system and pricing of oil in US dollars; unstable, corrupt, or lack of government in several major oil-producing countries; an increase of US production by nearly 6 million barrels per day since 2006; and an affiliation of OPEC with Russia and other non-member oil-producing countries.

Uncertainty regarding the effects of all this was evident at the conference in the range of oil price forecasts for 2019 ranging from $65 per barrel (Vitol) to $100 (Trafigura). Comments indicated confusion as to what will happen and how these organizations should respond; no one proposed any actions they or anyone else could or should take to establish stability and reliability of prices and supply.

A major disruptive event which these large organizations are just starting to come to grips with is the increase of US oil production, its persistence, and the resilience of the domestic US oil and gas industry. The return of the US to the top rank of oil producers was referred to in introductory comments as the “Return of the Jedi”. Although some large companies are becoming significant participants in the horizontal-well, hydraulic-fracturing development boom of very tight reservoirs they did not develop the methods nor initiate the Tight Oil revolution. They are now trying to understand it and figure out what to do about it. To know ahead of time what these companies would talk about in October 2018 one should have attended the Enercom Oil and Gas Conferences in Denver in 2011 to 2013. That is where independent US oil and gas operators present their plans. They created the Tight Oil revolution and are still driving it.

The other major Agent of Change affecting the industry is the Trump Administration. Conflicts, disagreements, sanctions, interest rates, and trade disputes affect major oil and gas producer countries, importer countries, consumers, businesses, independent and midstream operators, refiners, and third-world economies. Recent election results in several countries and a prolonged slide of oil prices below WTI $50/bbl have compounded uncertainties regarding the near-term course of the industry.

President Trump planned and announced a sanctions program for Iran that would reduce their oil exports “to zero”. He pressured Saudi Arabia and other OPEC producers to increase production to soften the effect of taking Iranian exports out of the market. After they did so, just before the deadline he issued waivers to China, India, and six other countries. These countries purchase more than 80% of Iranian exports; Iranian production will not be reduced as much as expected. The increased production which was not needed thus caused a perceived “glut” of oil on the market and rapidly falling prices. The waivers also made China a customer of Iran; they had quit importing American oil in response to Mr. Trump=s trade dispute. The US industry lost a customer to Iran.

The result of all this is that both oil-consuming and oil-producing economies are whipsawed by volatile pricing of the largest commodity in international trade – which will inevitability dampen economic growth. With its current high rate of oil production the US is in a strong position to revise its oil supply and price relationships and now is the time to do it. The WTI price dropped to $50 only six weeks after many forecasters were worried it would be more than $100 by year-end.

The US oil industry, by more than doubling oil production in the last 10 years made the US the world=s largest producer, ranking with Saudi Arabia and Russia, and gave Mr. Trump a strong geopolitical, economic, and political tool.

His reaction is to tweet:

“Oil prices getting lower. Great! Like a big Tax Cut for America and the World. Enjoy! $54, was just $82. Thank you to Saudi Arabia, but let’s go lower!”

Mr. Trump has done many good things for the US economy and some difficult things which are overdue in foreign policy but this tweet indicates Mr. Trump is getting very bad advice from people who do not understand the oil business. Probably economists or political campaign consultants who think a long term strategy is to the next election. These would be the same advisers who think it a good idea to draw down Strategic Petroleum Reserves to manipulate prices.

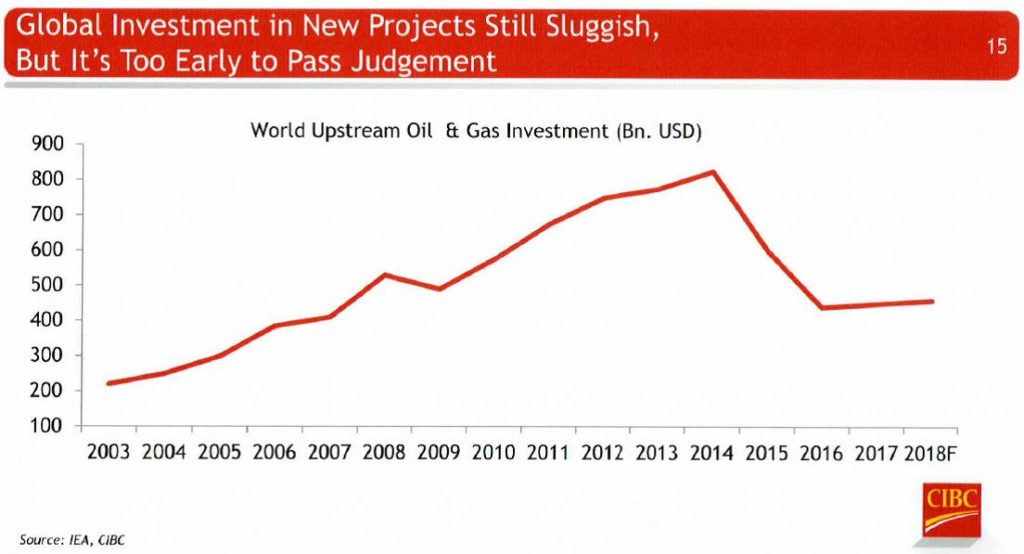

First, he is mixing up WTI domestic prices and Brent international prices. Second, after the domestic oil industry has done him a great favor he wants to repay them by driving them into bankruptcy and stiffing their creditors who paid for the drilling. Third, taxation is a power reserved for governments to raise money supposedly for the common good and payment is compulsory. Buying oil products is based on individual choices regarding usage and is voluntary. It is no more a tax than the cost of food. Some economists claim it is similar to a tax, however, and the Tax Cut comment indicates they are likely a source of his bad advice. Fourth, by forcing prices down he will stifle investment, curtail drilling, and production rates will decline to the point of oil shortages – probably in 2 to 3 years – and Mr. Trump will see oil at $150 per barrel before the end of his second term. At that point the Saudis will be remembering the double-cross over Iran early this month and will offer him suggestions where he might find sympathy; they have long memories about such things.

Oil industry policy objectives of an American President should be to establish reliable and adequate supplies at stable prices; not increase volatility in an already volatile and temperamental market place for a significant and necessary commodity and drive your own industry and allies into insolvency.

It is not unusual for American presidents to get bad advice, particularly about the oil business. The advice he is getting is reminiscent of the policies initiated by the US Government in response to the Arab actions in the 1970s. As Henry Kissinger noted: “The structure of the oil market was so little understood . . . . . the never-never land of national policy making . . . .”. Forty years later, we are still living with the results of those bad policy decisions; we do not need any more..

It is no wonder major players in the industry are now at a loss how to plan for the future and had little to say at the Oil and Money conference. They seemed to know something would happen but did not know what it would be. One cannot rationally predict impulsive actions based on bad advice. Any firm predictions or comments would be negated – and have been. They could not have predicted waiving the sanctions, a $25-per-barrel oil price drop, double-crossing the Saudis, US production continuing to increase, or a US President undermining the US industry.